SO WHY SHOULD WE CARE ABOUT POND WATER QUALITY?

You’d have to be living under a rock not to be aware of the significance of healthy water to life on the Cape. The well water that serves our homes and businesses requires it, our fisheries and shellfisheries rely on it, and its recreational and aesthetic values to tourism thrives on it.

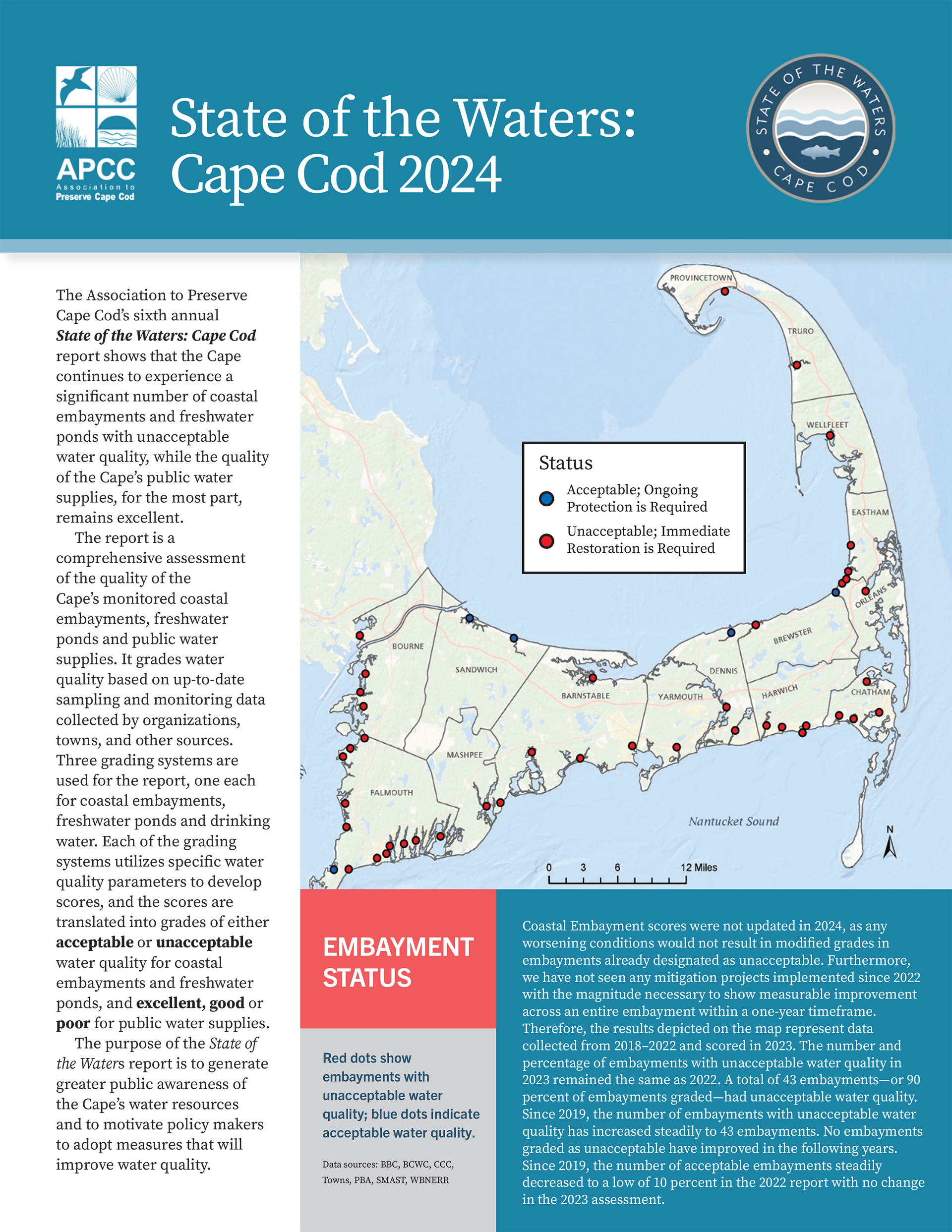

Yet despite this recognition, there have been, and continue to be, growing concerns about the health and quality of Cape Cod’s 890 freshwater ponds and lakes. Toxic algae blooms, pond beaches closed to swimming due to unsafe E coli levels, and other signs of impairment are becoming all too common in many areas of the Cape.

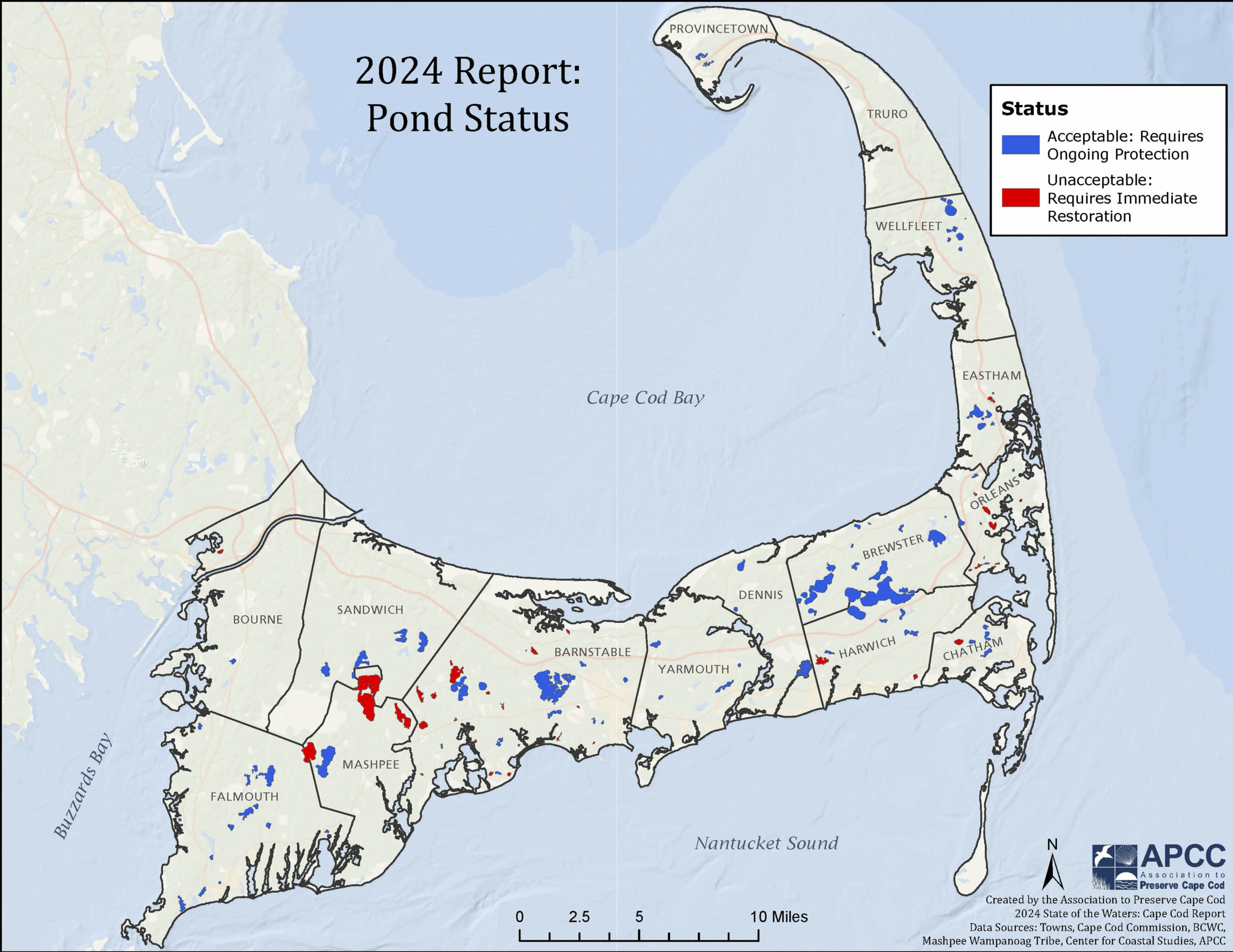

The 2024 ‘State of the Waters’ describes 28% of the graded Cape Cod ponds as “unacceptable” and noted “lack of sufficient water quality data” for most. Association for Preservation of Cape Cod (APCC) Executive Director, Andrew Gottleib, concluded: “more than half of our ponds for which we have water quality data are exhibiting signs of decline” and called on towns to make “a greater commitment to monitoring and restoring ponds”.

So … what’s a clean pond worth anyway?

Ponder these numbers from a recent Cape Cod Commission (CCC) economic valuation:

- 13-17 million people visit Cape Cod ponds and lakes annually

- 82% of Cape residents, seasonal homeowners and tourists reported some or frequent visits to its ponds and lakes

- 91% in the above categories agree or strongly agree that ponds and lakes are important to the Cape environment and expressed a willingness to pay a premium for living near them

- 84% agree that ponds and lakes are important to our economy

- $22,000 is the estimated average mark-up to the sales price of Cape homes that are closer to ponds with better water quality

- 660-830 jobs are attributed to spending tied to pond visits

- $70-89 million of the Cape’s GDP is associated with pond visits

Source: https://capecodcommission.org

Meanwhile - out here in Wellfleet …

When asked about the state of Wellfleet ponds, local pond expert John Cumbler offered: “the best thing that happened to Wellfleet ponds is what didn’t.” He was referring to the explosive growth and development that other parts of the Cape have seen (population quadrupling between1960 and 2000) that a large part of the Outer Cape (and nearly all its ponds) was spared thanks to the 1961 creation of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

Under the National Seashore’s watch and the highly-forested/minimally-developed nature of its watersheds, Wellfleet’s ponds have since come to be viewed and valued as among the most pristine on Cape Cod.

But challenges to that condition are emerging – more visitors using the ponds, erosion of pond banks and shorelines, and cumulative impacts of deficient septic systems in homes bordering the ponds -all of which contribute to greater nutrient loading, the consequent escalation of toxic cyanobacteria bloom events and other water quality impairments.

Wellfleet ponds watershed view (photo by Steve Heaslip, Cape Cod Times)

A summer day at Long Pond (photo by Sophia Ruehr, Provincetown Banner)

A FEW KEY THOUGHTS FOR POND-ERING ON THE OUTLOOK FOR OUR WELLFLEET PONDS

-

Our vegetated pond buffers are currently less that 25% disturbed, but steps will need to be taken to maintain and increase these buffers to healthy water quality.

-

Major reductions in pond acidity have created conditions more favorable to growth of phytoplankton and other plants that serve as the base of the pond food chain — an unintended consequence of the Clean Air Act.

-

Those changes, along with elevated water temperatures and nutrient inputs to the ponds, are triggering increases in pond plant growth and the likelihood of harmful algal blooms.

-

Climate change is altering the summer and winter thermal stratification regimes in some of our deeper ponds, leading to anoxic (low dissolved oxygen) conditions at their bottoms. See “Drilling Down on the Data” for details on impact of low dissolved oxygen.

-

Ponds are delicate and fragile ecosystems that serve as vital windows to the health of our water supply.

-

Climate change is going to make maintaining the health of these ponds more difficult and the need to monitor and manage them more crucial.

-

While they may look clear and pristine to the naked eye, there are changes going on with the chemistry of our ponds that we may not see, but will need to remain vigilant in monitoring

-

If we were to lose the pristine condition of our Wellfleet ponds, it will be impossible to get it back!