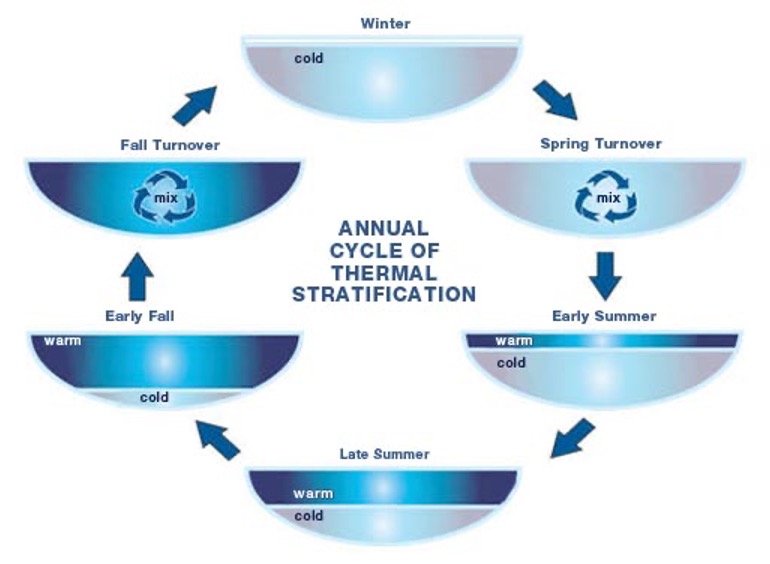

Our ponds, like our land areas, undergo changes through the seasons, some of which are obvious to the naked eye, and others not so much. The graphics below highlight one aspect of the latter.

Did you know?

Some ponds have thermal layers

Ponds that are 20 feet or more in depth often form distinct layers of differing temperatures. This is called thermal stratification. Twice a year – during spring and fall – these layers mix, increasing oxygen levels and redistributing nutrients throughout the pond.

WINTER: As we move into winter, the water often separates into thermal layers again. In ponds where temperatures drop below freezing, the separation of layers is dramatic, with the water being warmer near the bottom and colder on top. Once the surface water temperature drops to 4℃ / 39.2°F (the temperature at which fresh water is densest), the top layer sinks to the bottom. As water above this layer continues to cool, the pond may begin to freeze, leaving the remaining less-dense layer of ice on its surface.

FALL: During October and November, temperature layering begins to weaken as cold nights cause water at the surface of the pond to cool and approach the density of deeper water. As densities become more equal, it takes less wind energy to mix the water. Water from the bottom of the lake rises to the top, and water from the top of the lake sinks to the bottom. Strong northerly autumn winds contribute to the mixing. The process allows for oxygen to be replenished and nutrients to be distributed throughout the pond.

SOMETHING TO WATCH OUT FOR?

One possible consequence of warming pond temperatures is an increase in the duration and depth of the warm water layer further into the fall. This in turn could lead to an increasing frequency and intensity of harmful cyanobacteria blooms.

SPRING: Every spring (and fall), a natural process called turnover occurs in deeper Wellfleet ponds, resulting in mixing of the entire water column. This temperature-driven process mixes oxygen and nutrients throughout the pond from the bottom to the surface, enabling aquatic life to inhabit the entire pond as oxygen becomes more available.

SUMMER: In late spring or summer, as waters warm, the ponds begin to stratify or form distinct thermal layers. Warmer and less dense water floats on the top of cooler, denser water at the bottom, creating a layer of warmer water on top and cooler water below. These layers, along with the lighter winds we tend to have at this time of year, prevent the lake from mixing and aerating. The ponds generally remain stratified throughout the summer.

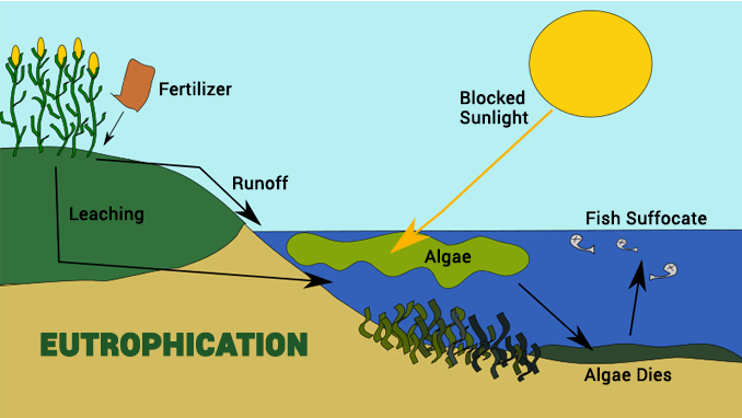

Natural eutrophication is the gradual enrichment of a water body with nutrients over long periods (typically centuries) as the basin fills with sediment and nutrients. Though essential for plant growth, an overabundance of nutrients in water can have harmful environmental and health effects. An excess of nutrients in a pond – primarily nitrogen and phosphorus – speeds up eutrophication.

Algae feed on the nutrients, growing, spreading, and turning the water green or other colors. Algal blooms can block sunlight, preventing aquatic plants from photosynthesizing, Some species of algae may even release toxins into the water. When algae die, they are decomposed by bacteria. This process consumes the oxygen dissolved in the water that’s needed by fish and other aquatic life. If enough oxygen is removed, the water can become hypoxic, where there’s not enough oxygen to sustain life, resulting in the death of aquatic organisms.

Human-activity induced eutrophication: Too much of a good thing can be a problem. Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, occur naturally, but human activities in and around the ponds, and on the lands that drain into ponds, can elevate nutrient levels in the ponds to levels that upset the ecological balance. This influx of nutrients occurs via direct runoff or leaching (the movement of soluble nutrients as water percolates through the soil). Human related sources include the fertilizers we put on our lawns and gardens, wastewater from septic systems, emissions from automobile exhausts, pet wastes and other runoff-related inputs.

Excess nitrogen and phosphorus reaching ponds from these sources can trigger algal blooms. The most frequent and harmful algal blooms (HABs) are caused by cyanobacteria, which produce toxins that are potent enough to harm human health. For more information on this, click here.

Toxic algae bloom in Cape Cod pond (image courtesy of APCC)